We’re not getting many vampire movies these days. And that’s a shame. It’s not like they’ve gone anywhere, they never really do. But everything in the horror genre moves in cycles. It seems like only one sub-genre can ever really be popular at one time. This is absolutely true for vampires, who have been around as long if not longer than any other monster in fiction. They predate the written word, with legends ingrained into the history of every single culture on earth.

And the vampire, as we knew it, is a very different thing from the vampire as we know it now. People love to blame Twilight, even now that that craze is well and truly over. They love to say that Stephanie Meyer de-fanged vampires by making them teenagers, channeling their supernatural state of being into angst, bringing them into the sunlight and making them sparkle. But things had been moving in that direction for a long time. Everything that’s happened to vampires over the years has been a very natural progression.

Going back to early English literature, vampires were basically ghost stories. There wasn’t a lot of difference. They were an old concept even then, and represented horrific stories of the dead returning to life to haunt and feed off the living. The first literary attempt to bring them into the modern era was actually Dracula. It’s surprising, I know, because Dracula is what we so often think of as the traditional archaic vampire story. But Stoker did a lot of research, drawing from fiction that had come before him like Carmilla and Varney the Vampire. The gothic setting of the foggy Carpathian Mountains, the crumbling, dark castle of the Count, these were all pretty well associated with vampires even then. But people tend to forget, or simply may not know, that Dracula is only set in Transylvania for the first four chapters.

Obviously, the success of Dracula launched vampires into the mainstream. The book wasn’t an overnight success, but it built up an audience over time, leading to several stage adaptations and of course an eventual film. The first of such—an unofficial adaptation because it could not get the rights—was Nosferatu. That film really showcases just how much vampires have changed in the span of about a century. There’s nothing attractive, alluring or sympathetic about that creature. In that way, he’s actually very close to the creepy vampire of the book.

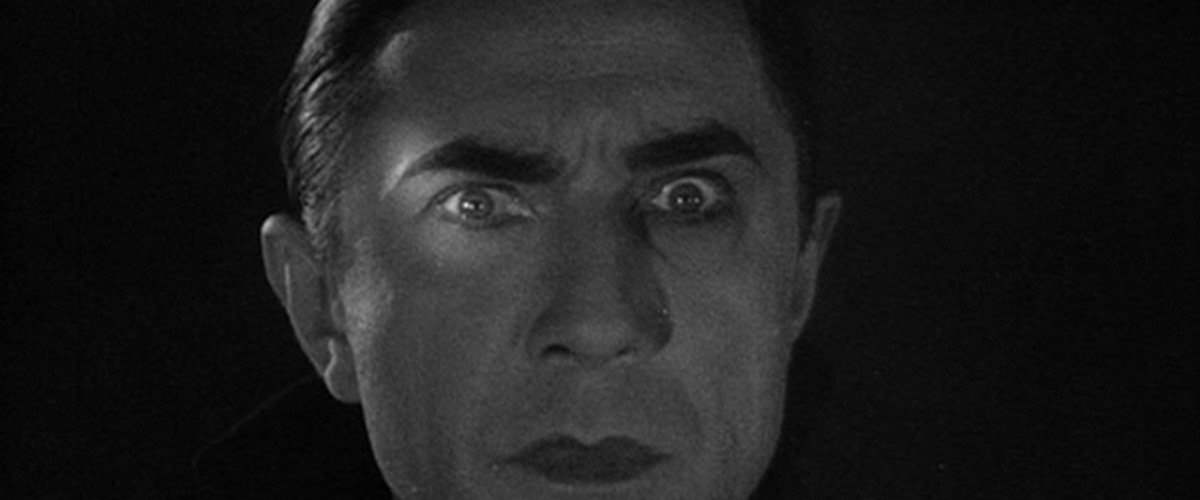

On film, the first attempt to romanticize the vampire came in Universal’s marketing campaign for the classic 1931 version of Dracula. It was billed as “the strangest love story ever told” but was really anything but. Dracula’s not any more romantic in that one than he was in Nosferatu, even if he doesn’t look like a pallid rat monster this time around. Lugosi barely exchanges dialogue with Helen Chandler’s Mina and she expresses no interest in him, whatsoever.

Still, that was when people first started to get the idea that the vampire might be something of a romantic figure. Universal launched several sequels to Dracula throughout the thirties and forties, with Lugosi eventually being replaced by John Carradine. The popularity of the classic monsters began to wane in the late forties and by the time the fifties were in full swing, we weren’t really seeing any vampires at all. If there were any vampire stories, they’d be in the form of comics like Tales from the Crypt and Vault of Horror, but on the screen the fifties were totally dominated by science fiction.

Still, that was when people first started to get the idea that the vampire might be something of a romantic figure. Universal launched several sequels to Dracula throughout the thirties and forties, with Lugosi eventually being replaced by John Carradine. The popularity of the classic monsters began to wane in the late forties and by the time the fifties were in full swing, we weren’t really seeing any vampires at all. If there were any vampire stories, they’d be in the form of comics like Tales from the Crypt and Vault of Horror, but on the screen the fifties were totally dominated by science fiction.

They didn’t make a comeback until the end of that decade with Hammer’s Horror of Dracula. I would be willing to say that the Hammer age of vampires was their most successful period on film. It defined them for a long time. Through the sixties and into the early seventies, vampire movies were taking off like gangbusters. Christopher Lee’s Count was very different from Lugosi’s. As much as people were captivated by Lugosi’s performance, you never actually saw him do anything. You never saw him bite anyone. Hell, Lugosi didn’t even have fangs.

Christopher Lee’s Dracula with blazing red eyes and blood dripping from his fangs is a very different image. He could be cold and commanding one moment and a snarling monster the next. I think, personally, that there’s a reason he wound up playing the vampire more times on screen than any other actor. His version of it defined vampire cinema for a generation, and was simply unforgettable.

Christopher Lee’s Dracula with blazing red eyes and blood dripping from his fangs is a very different image. He could be cold and commanding one moment and a snarling monster the next. I think, personally, that there’s a reason he wound up playing the vampire more times on screen than any other actor. His version of it defined vampire cinema for a generation, and was simply unforgettable.

While the concept had been teased in the past, the first major reluctant vampire made his appearance on the small screen in the soap opera Dark Shadows. Barnabas Collins was introduced as a pretty standard vampire mixed in with a long history with the Collins family, but became a more complicated character over time as he needed more to do. He wound up being the first major pop culture vampire that cursed his condition and felt genuinely tortured.

While Salem’s Lot really tried to take vampires back to their horror roots in the seventies, the genre kept pushing in the direction of creating sympathetic monsters. In George Romero’s Martin, the titular character isn’t even really a vampire. He only thinks he is. Technically, he’s a serial killer, but he’s such a fragile, sympathetic person because you can see exactly how he came to be that way. Martin speaks to the dangers of a fundamentalist and superstitious upbringing. His uncle is very much a man of the old country and if the legend is that Martin is to be a vampire, then it must be true, and knowing no different, Martin acts on the only thing he knows he’s supposed to be.

Martin really represents how perceptions of vampires had changed by that point in the seventies, but it didn’t have any impact because the movie didn’t make any money and many people still aren’t aware of it, despite it being one of Romero’s best.

Martin really represents how perceptions of vampires had changed by that point in the seventies, but it didn’t have any impact because the movie didn’t make any money and many people still aren’t aware of it, despite it being one of Romero’s best.

There was, however, a book that came out in 1976 that pretty much defined vampires as we’ve known them ever since: Interview With the Vampire by Anne Rice. By the time the film adaptation came out in the nineties, Rice’s influence was extremely widespread.

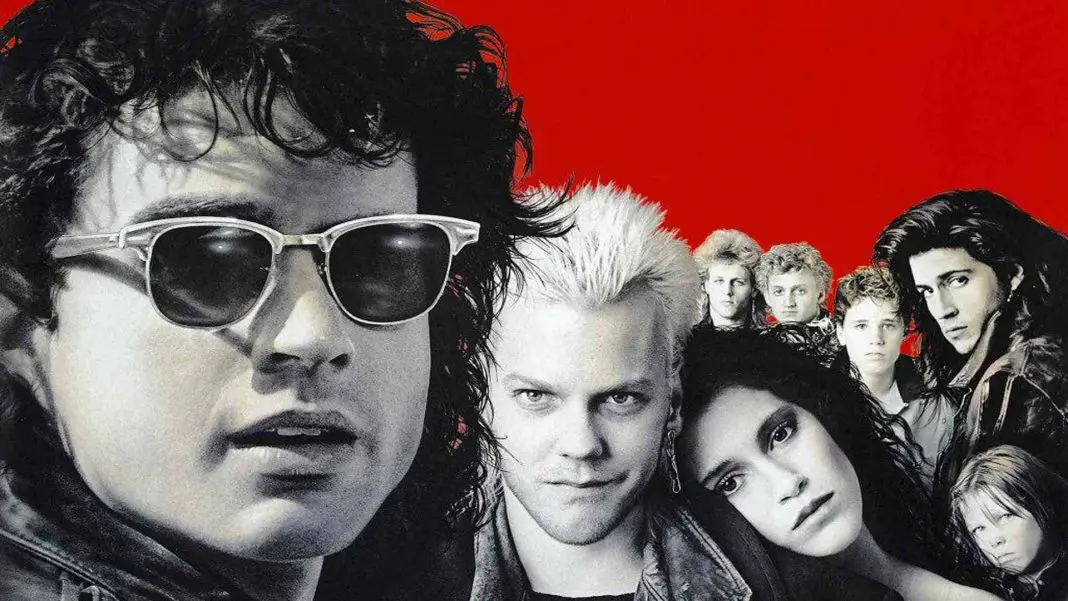

Even the vampires of the eighties show a clear through line to now. Fright Night was about taking the conventions of the Hammer features and updating them for the modern era, much in the same way that Scream would later do for slashers. Near Dark harkened back to Martin, in a way, given that we never really see fangs and the characters are never referred to as vampires. The Lost Boys is a favorite even now. Teenagers still go back and watch this one as though it’s a rite of passage. And I hate to say it, guys, but there is a direct line between The Lost Boys and Twilight. Both hit a lot of the same notes, both touch on the same basic themes, the only real difference is that one was really good and one was really bad. The Lost Boys doesn’t forget to be a horror movie while it tries to be a teen movie, which helps a great deal.

The success of these gave us a lot of teen vampire comedies by the end of the eighties, like Once Bitten and My Best Friend is a Vampire. Marry that with the heavy romantic elements of the nineties—namely Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Interview With the Vampire—plus the action-heavy elements that would come later with the likes of Blade, Underworld and virtually everything we got through the late ’90s and 2000s, and you’ll see the blending of every trope that we still know to this day. Vampires have not strayed from the path. They’ve only become a cocktail of everything we’ve seen in the past couple of decades.

The success of these gave us a lot of teen vampire comedies by the end of the eighties, like Once Bitten and My Best Friend is a Vampire. Marry that with the heavy romantic elements of the nineties—namely Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Interview With the Vampire—plus the action-heavy elements that would come later with the likes of Blade, Underworld and virtually everything we got through the late ’90s and 2000s, and you’ll see the blending of every trope that we still know to this day. Vampires have not strayed from the path. They’ve only become a cocktail of everything we’ve seen in the past couple of decades.

This could worry some people, and that’s understandable. We horror fans like vampires to be a part of the horror genre, we want them to be scary. But I think that time will come around again. It’s never completely over. Someone will always be there to make a film like 30 Days of Night or Stake Land to strip the romantic elements away completely. And projects like that also allow for those softer features to have their place.

Right now, we’re not really seeing any vampire movies at all. But I don’t think that’s cause for alarm, either. If there’s anything I’ve learned, watching these films all my life, it’s that they never stay dead for long.