Horror tends to move in cycles. We’ve all seen it. Things go in and out of fashion, some styles are embraced for a few years and then tossed away, anything can come back at the drop of a hat. The past decade saw a huge resurgence of 1970’s horror. In America, that seemed to come about in the form of remakes. Every title from that time in the genre’s history was being dusted off again. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Amityville Horror, The Hills Have Eyes, The Last House on the Left, they wee all being targeted for remakes. But simply updating these features for new generations didn’t do much to explore what made them special to begin with. For that, you had to go to France. New French Extremity was the last thing that anyone expected, but it proved to be one of the most important horror movements of its decade and possibly the most influential.

New French Extremity wasn’t just a throwback to exploitation cinema. That was a small part of it, perhaps, that these new filmmakers were influenced by the American exploitation classics they had seen when they were young, but more than anything they felt a need to explore the ideas that those movies explored. They had a reason to go back to that and create a form of cinema that was, to paraphrase film scholar Tania Modleski, adversarial to society.

These films didn’t push boundaries, they broke them. They were more visceral and more disturbing than anything being produced in America at the time. And they also, somewhat ironically, served as the partial reason for so many American remakes. That was the only way we could try to keep up. Now we’ve come full circle, with the first American remake of New French Extremity in the form of Martyrs.

The New French Extremity films also divided fans and moviegoers somewhat, with some saying that these features went too far and others saying they went as far as they had to. While many of them were incredibly hard to watch, I side with the latter train of thought. Because of that mentality, though, these were a source of much controversy, especially in their native country. But that’s not why they were made.Like the American exploitation pictures, they were made to talk back to a political and economic climate that the filmmakers considered to be conservative and threatening. The biggest reason for horror to move in cycles will always be the resurgence of old fears and old problems. The 2000’s were the 1970’s all over again for the entire globe.

Haute Tension explores some of these fears in an incredibly effective way. This is a film about smothering and controlling women, about what happens when you teach people to suppress their impulses and repress their being. It’s a rebellious picture, powerful and hard to watch at the same time. Yet it has been criticized by fans for its ending, which is strange, given that the ending is its thesis. It’s the entire reason for the movie’s existence. Haute Tension has the tone of early exploitation cinema down perfectly, but it’s not interested in simply being another feature of that type. Alexandre Aja had his own unique vision and his own reasons for making it. In particular, there’s a lot to interpret about repressed sexuality. Not only is the lead character Marie harboring romantic feelings for her best friend, Alex, but those feelings as well as her murderous urges are personified in the form of a typically brutish man. It’s a subversive play on aggression and impulses, as well as the things we typically consider as male and female.

Related: The Intensity of High Tension: A Look at Plagiarism in the Horror Genre

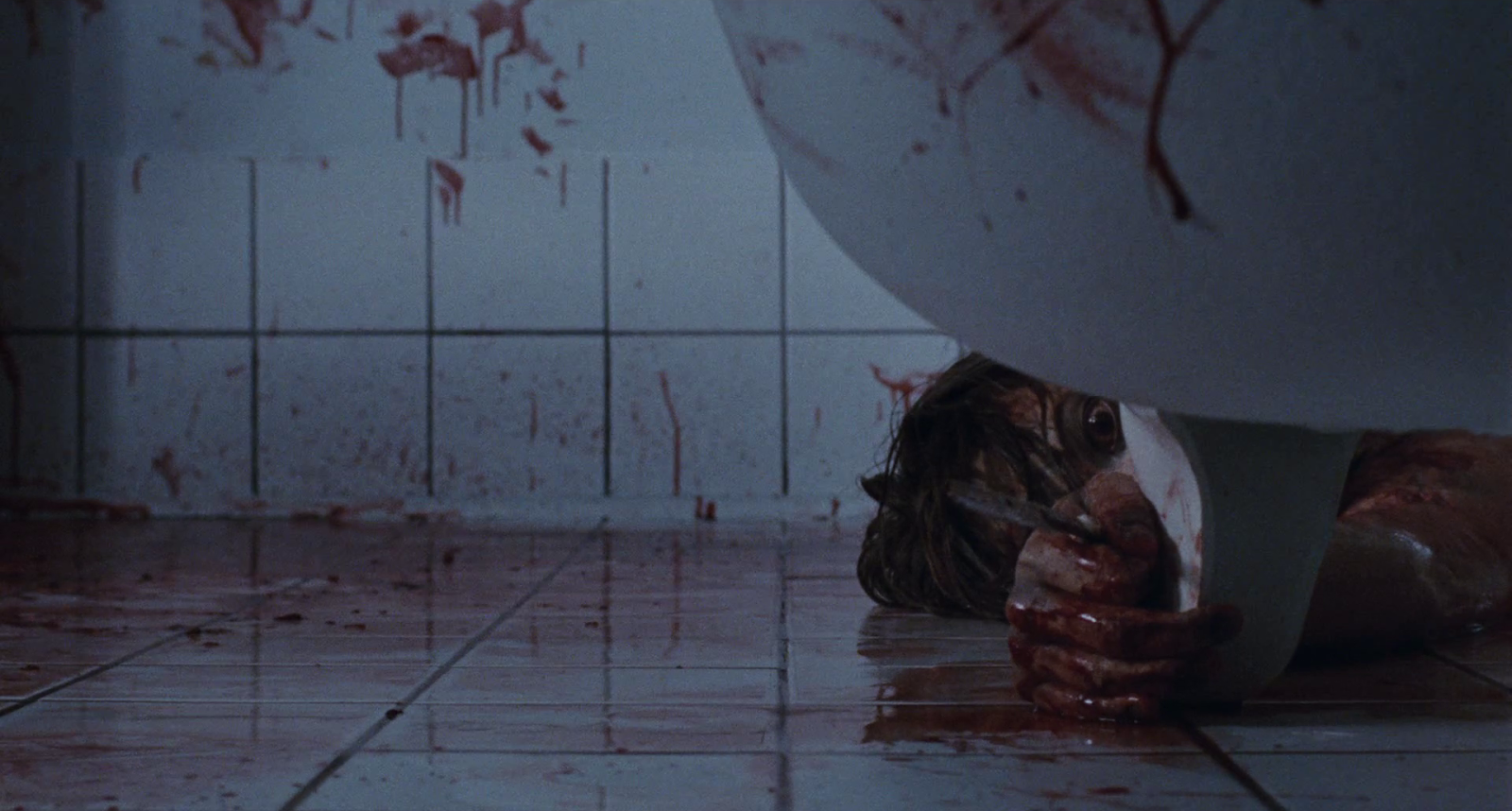

Pascal Laughier’s Martyrs is among the most disturbing of the New French Extremity movement. This film begins with a horrific act: A young girl escaping her kidnappers. It’s an intense scene that could serve as the ending to many horror movies, but the fact that it is the beginning means it only gets worse from there. It does, too, and it gets bigger as well. There’s no specific kidnapper but rather an Illuminati-esque secret society that systematically oversees the kidnapping and murdering of young women in order try and find out what’s waiting on the other side by recording the victims’ final thoughts as they die. Imaginative? Yes. Also brutal. Martyrs is painful to watch but also extremely painful to sit through on an emotional level. The psychological damage these girls suffer is clear and their torture is so drawn out. But that doesn’t mean Martyrs isn’t an important movie.

Pascal Laughier’s Martyrs is among the most disturbing of the New French Extremity movement. This film begins with a horrific act: A young girl escaping her kidnappers. It’s an intense scene that could serve as the ending to many horror movies, but the fact that it is the beginning means it only gets worse from there. It does, too, and it gets bigger as well. There’s no specific kidnapper but rather an Illuminati-esque secret society that systematically oversees the kidnapping and murdering of young women in order try and find out what’s waiting on the other side by recording the victims’ final thoughts as they die. Imaginative? Yes. Also brutal. Martyrs is painful to watch but also extremely painful to sit through on an emotional level. The psychological damage these girls suffer is clear and their torture is so drawn out. But that doesn’t mean Martyrs isn’t an important movie.

Exploitation horror is anarchistic, it pushes back against society. Martyrs is a perfect example of this because the film’s villain is society itself. This is not a madman, but a system of madmen and while it’s exaggerated and fictional, most of the points ring true. The people who are killing these girls have essentially formed their own culture and they have no one to answer to. They’re the rich and powerful, they’re the people at the top.

Alexandre Bustillo and Julian Maury’s Inside uses New French Extremity to explore the tried and true conservative topic of what to do with a woman’s body. It’s about a pregnant woman who becomes the victim of a home invasion in which the attacker is attempting to steal her unborn baby. The film is so minimalistic, yet so haunting and definitely one of the most disturbing to come out of the French Extremity movement. It’s worth noting for being one of the few horrors where both the victim and the attacker are female as well.

While other countries were producing great content in the 2000’s, French filmmakers were truly pushing the boundaries. Whether they be subject matter, technology or taste, they were exploring how much further cinema could go than it had in the past. Just as the films of the 1970’s had done. They took the medium back to a period of exploitation that had also served as a renaissance to create a new movement that defined the decade and has proved to be the most influential of its time.