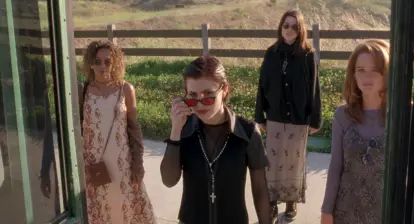

I was 8 when The Craft first came out, which meant there wasn’t a hope in hell of my being allowed rent it from the video store. But the cover art always intrigued me, those impossibly cool Goth chicks strutting toward the camera with the lightning bolts (denoting their otherworldly powers) swirling all around them.

I knew it was special, that it would speak to me in ways hitherto unknown. And, around eight years later, my suspicions were confirmed (unlike Idle Hands, which had a similarly cool box).

I have a lot to thank this movie for; there’s a reason I go back to it again and again, how it still feels relevant to me the older I get. It’s timeless, and its feminist message is one that will hit home with young girls and women for as long as we watch movies.

But, even more importantly, The Craft is a rallying cry for freaks, for being different. Nancy’s defiant “We are the weirdos, mister” is such a classic line, it’s been emblazoned on apparel from cult goth clothing line Killstar, alongside her image as the undisputed queen of goth kids all over the world. Er, apart from Siouxsie, that is.

The Craft is hugely progressive in many ways, insanely ahead of its time in others. From the female-focused storyline, to the casting of an African American actress in one of the lead roles, all the flick is really missing is a female writer or director. Thankfully, its female power message shines through in spite of the amount of testosterone behind the camera.

We watch as Nancy attempts to fool Sarah’s crush into sleeping with her instead, how Bonnie starts to become vain and self-involved once her scars are healed, and the jealousy that leads to the girls taking revenge on Sarah once it becomes clear that she’s the most powerful of them all.

The core message is: It’s what inside that counts, even if what’s inside is really horrible. The core group are both soul sisters and mortal enemies. And, as far as bullying is concerned, The Craft doesn’t pull any punches. The final showdown plays off Sarah’s pre-suicide hallucinations, while Nancy tells her in no uncertain terms to “get on with” killing herself, echoing the future sentiments of millions of Internet commenters.

Rape culture is represented via Chris’s character and his spreading of a rumour about Sarah, supposedly, sleeping with him, being terrible in bed and then stalking him after the fact. The idea of something being taken out of a woman’s control and used against her is explored here in an honest way rarely seen elsewhere. It’s painful, it’s harsh and it’s wholly unfair.

The self-harm sequence, which sees Sarah explicitly slice her wrists open, would never pass in today’s PC world (see: Axelle Carolyn’s unfairly censored Soulmate). But it’s so intrinsic to her story, and to her eventual emergence as the strongest power out of all four girls, that is has to be as graphic and stomach-churning as it is.

The closest modern equivalent of The Craft is arguably Mean Girls, which explores the toxic nature of gossip, bullying, and female friendships when loyalty to the group is seen as the utmost and one woman unexpectedly excels above the others. In both movies, the difficulty of being a teenage girl is represented in different, albeit similarly surreal, ways.

The closest modern equivalent of The Craft is arguably Mean Girls, which explores the toxic nature of gossip, bullying, and female friendships when loyalty to the group is seen as the utmost and one woman unexpectedly excels above the others. In both movies, the difficulty of being a teenage girl is represented in different, albeit similarly surreal, ways.

And, in both cases, it’s the new girl who changes and develops over the course of the story, committing minor social crimes in order to discover who she really is, before emerging victorious after cleansing her conscience. In The Craft, Sarah is the only one who still has her powers in the end, because she’s pure of heart. In Mean Girls, Cady realises who her true friends are and settles down into a happy life with them.

Sarah is kind of the original Bella Swan; sullen, emo, a bit bland and a blank slate until she meets the rest of the coven. She’s a decent audience insert because it’s easy to see this new world through her eyes, even if Sarah isn’t the easiest person to understand at times.

More memorable is Nancy, played as only she could be by real-life Wiccan (and loon–her appearance in Richard Stanley documentary Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau is representative of her particular band of eccentricity) Fairuza Balk. Nancy is the perfect villain; we hate her but she’s still desperately cool.

She also has the harshest, and most realistic, familial situation with a deadbeat mother who chooses men over her and no real support system at home. It makes sense that Nancy lashes out the way she does, her teenage angst coming out in violent bursts of untapped energy. Of course Nancy can’t understand, just as none of us could when we were her age and everything seemed to be going impossibly wrong. Rather than hit us over the head with a grand, unearned redemption, though, the flick ends with the baddest bitch in school rotting in an insane asylum–a damning indictment of what happens to those who choose the wrong path.

Of course Nancy can’t understand, just as none of us could when we were her age and everything seemed to be going impossibly wrong. Rather than hit us over the head with a grand, unearned redemption, though, the flick ends with the baddest bitch in school rotting in an insane asylum–a damning indictment of what happens to those who choose the wrong path.

The Craft is of huge, continuing cultural significance, its representation of alternative culture handled with zero Hollywood sheen. Referenced in everything from Wild Things to Little Mix’s Black Magic music video, the movie is still the calling card for any teenage girl looking to make her school uniform a bit cooler.

Its place in horror is of interest too, defined as it is as more of a fantastical teen movie than full-on genre fare. The roots are there, though, stars Neve Campbell and Skeet Ulrich having played a couple in Wes Craven’s seminal Scream that same year.

The Craft also boasts the most terrifying (and real!) usage of snakes on-screen this side of Indiana Jones (star Robin Tunney reportedly thought fake creatures would be used). Arguably the scariest element, however, is how realistic its depiction of the horror of teenage life is, but at least we come out of it knowing we’re not alone.

Twenty years later, if there’s one thing The Craft has taught us–aside from the fact that vinyl is best accessorised with more vinyl–it’s that we are all the weirdos, mister.