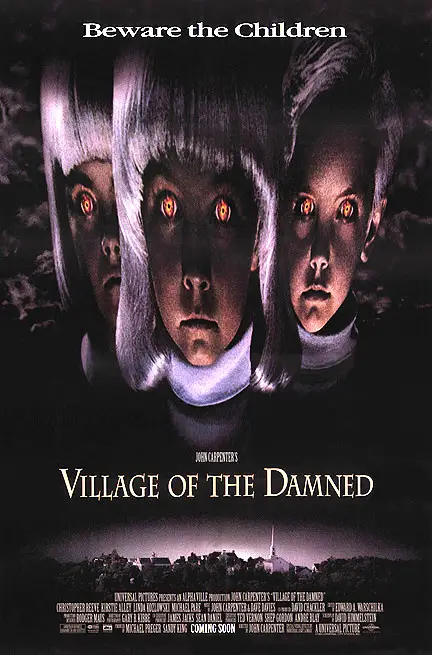

There are a lot of horror movies that flew under the radar. For whatever reason, they never gained much of even a cult following. Even John Carpenter fans don’t talk much about Village of the Damned. It’s not as maligned as Ghosts of Mars or The Ward, it simply doesn’t come up. Even the director’s rabid followers don’t remember the movie. But there’s a lot in Village of the Damned to like.

It’s probably one of the most overlooked horror movies of the 1990’s, in fact. Even though it retreads the story of the original, it adds a lot of substance to the female characters (who, despite their necessary role, were all but forgotten in the original) and still contains a lot of typical Carpenter style. Still, it was pretty much a dud when it was released in theaters. Most of the reception was negative, but there were some positives as well. The New York Times called it Carpenter’s “best horror film in a long while.”

Even some of Carpenter’s best defenders, though, call this his weakest film. And while it was not the movie he set out to make and was rife with production problems, it doesn’t deserve the attention that it gets.

The plot should be familiar to all those aware of the 1960 original. One day, out of the blue, there is a blackout in the town of Midwich (moved from an English village to a Northern California town here) and every single citizen falls asleep. The movie is criticized for its out of place feel. It’s a modern update, but just about everything about it feels like the early 1960’s. I think that is one of the film’s strongest benefits. It provides atmosphere and a sense of style, it’s a tonal return to the films of the era in which the original Village of the Damned was made.

The opening of Village of the Damned is its strongest point and definitely the highlight of the film. It opens with a literal bang. Because everyone falls asleep at once, some people are barbequing, some people are driving, and thus a lot of people actually die during this time. There are a lot of unexpected set pieces that hit all at once and put the audience on the edge of their seat right at the start of the film. After that, though, is what really sets the plot in motion. Only a few short days later, ten of the local women test themselves for pregnancy, virtually all at once. Every single pregnancy is dated to the day of the blackout.

Kirstie Alley’s Dr. Susan Verner soon arrives to assess the seen, as the women in town and their miracle pregnancies are of keen interest to medical science. All of the women are somehow, subtly guided by the infants growing inside them, or whatever they are. They all are having the same dream of a dark, gray sky. Something beyond guiding them through this, step-by-step, hand-in-hand. That’s one of the strengths of Village of the Damned, this unknown thing from beyond that sets all of the events in motion. Even though Verner promises government compensation for the women who decide to keep their babies, she is shocked when they all do.

The women give birth, all but one, the infant who died in childbirth. Right away, things aren’t normal. The children all begin to develop very quickly. Before they can walk, they can spell their name. They all have the same white hair. In fact, they all look almost identical. And they have powers, even before they can talk, they can read minds and control them. Young Mara, the leader, makes her mother stick her arm into a scalding pot of soup simply because she didn’t like it. And when that is not enough, forces her mother to walk off a cliff to her death.

There’s a sudden jump in time, about six years, until the children are actually children and not just toddlers. The recap of time passage is a smart one, though, with Verner explaining everything that’s happened in that time with a report being made to her superior officers.

The children come to be feared by everyone, especially their own parents. Christopher Reeve is a solid, classical lead as local town doctor Alan Chaffee. He’s not a typical Carpenter lead. He’s not as abrasive, he’s not as much of a loner, and therefore he’s honestly not as interesting as the Kurt Russell characters. But he’s serviceable, certainly for this more small-town type of story. This was Reeve’s last performance before his terrible accident and as such it’s not an awful way to go out. Because he does do a good, sincere job.

The only real subplot among the children themselves is found in young David. He has the intelligence and the abilities of the other children, but he also has a sense of empathy and growing humanity that they do not possess. He feels emotions, he knows loss. The children have already paired up among themselves. There are four boys and four girls, and there is David. The infant that died in childbirth was supposed to be with him. And now he is out of place among his own kind, however evil they are.

His mother (if you can call her that) sees his growing humanity and tries to encourage it, make sure he doesn’t deny it, while the other children simply want David to learn his place. There’s a bit of a free will debate there, but the themes in this movie are light, and that’s one of the things really bogging it down.

The children’s general appearance in the movie have been criticized relentlessly. But it works with the film’s retro visual style. And their costuming is a great use of color symbolism. The movie is a color remake of the original, and the town (while dusty) has color as do the people in it. But the children are all nonetheless black and white. They wear matching gray uniforms, they all have pale skin and they all have white hair. The only color attributes that are given to the children are their eyes. When they use their power, their eyes may flash green or red and when they use enough power to kill someone, their eyes are taken over by white light that seems to come from somewhere inside of them.

One thing that would have been great for Village of the Damned would have been if the nature of the children was left unknown. Not knowing is always scarier than knowing. Carpenter learned this with Michael Myers, yet does not apply that same solution here. There’s a bit of exposition between Verner and Chaffee, who explains that the baby that died during childbirth (which had been reported to be taken away for an autopsy) and the infant’s corpse—which had been kept in a jar—is revealed to be a fairly traditional looking alien. It’s an effective moment in the sense that it was teased through most of the film, but it would have been much better not knowing.

The film ends like it begins, with a lot of explosions. The police arrive to deal with the children, but a moment of mind control and then they’re all shooting each other. An angry mob, led by wife of the local preacher (played by a miscast Mark Hamill) and that goes just as well, as the children convince her to light herself on fire. The church blows up and the children are killed, but David and his mother survive, with the promise that they will go somewhere where nobody knows who they are.

Those who say that the movie stays too true to the original are right in some respects—it is, after all, different from the complete do-over that was The Thing—but are forgetting that one of the movie’s major focuses is on David and his developing humanity. And David was never a character in the original movie or the book that it’s based on.

The biggest positive that Village of the Damned has going for it is the score. It was one of the last scores Carpenter ever did (after this would come Vampires and Ghosts of Mars, and that would be it) and it’s one of the most underrated, easily. The music is haunting, atmospheric with a melody that plays sparingly throughout. Without the music the movie would have worked a lot less. The score alone is worth checking out.

Overall, the movie is not Carpenter’s best, nor his worst. It’s worth checking out at least once, though, and can be a pretty fun re-watch, but it certainly does not have the legacy that the original film has.