There are several characters we think of when we think of Dracula. First and foremost, there’s the Count himself. The most famous vampire in the history of literature, film, television and so on and so forth. Then, we probably think of Van Helsing if not jumping straight into the Count’s spastic sidekick, Renfield. All three characters are iconic in their own right. All three have been played by dozens of different actors over the course of nearly a full century.

But for me, Dracula is every character. It’s not just the Count, the hero and the crazy person. They’re incredibly important. Each character serves a purpose in that story, to drive that plot along, however that plot gets restructured and repurposed. But Lucy Westenra serves more of a purpose than most. For all intents and purposes, she’s the character that drives the bulk of the story. She is the one who first gets targeted by Dracula, she’s the one who becomes mysteriously ill, bringing Van Helsing into the story.

Most importantly, Lucy shows us the process of becoming a vampire and makes the stakes clear—no pun intended. Through Lucy, we see why becoming a vampire is a terrifying prospect. Stripped of the subtext and the fact that this is, essentially, a female main character reduced to a plot point and being saved by a band of male heroes—stripped of any of that, this is essentially possession as a disease. This is a disease that doesn’t just kill you, it hollows you out and fills you with something else.

Considering that Dracula is the most filmed novel in history, Lucy has undergone a variety of drastically different interpretations over time. Many of these adaptations combined characters together and shifted plotlines around. In the original, unofficial film Nosferatu, there’s no Lucy stand-in to be found. In Universal’s original, official classic, Lucy’s plotline plays out similarly to the novel with one major exception: it all takes place off screen. We never see her become a vampire, we only hear briefly about her returning after being a vampire, we never see her get staked and finally laid to rest. It is one of many major events in that movie that we as an audience don’t actually get to bear witness to.

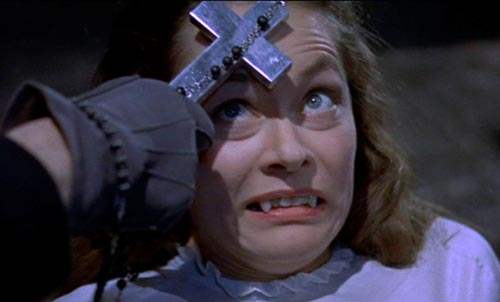

It’s not until Hammer’s Horror of Dracula that Lucy’s transformation into a vampire really becomes a prominent event in the movie. It’s one of the better sequences in one of the better adaptations. Peter Cushing’s extremely capable, heroic Van Helsing knows exactly what to do now that Lucy has transformed into a vampire. The image of the cross burned into her forehead is so iconic that it has been referenced in such huge horror classics as The Evil Dead and Fright Night.

In the 1979 John Badham version of Dracula, starring Frank Langella as the Count, Lucy actually takes center stage as the main character. This is primarily because she and Mina swap names—and this isn’t the only time this has happened. In this version, Lucy is the fiancée of John Harker and Mina is the daughter of Van Helsing who takes Lucy’s place as Dracula’s first victim.

In the 1979 John Badham version of Dracula, starring Frank Langella as the Count, Lucy actually takes center stage as the main character. This is primarily because she and Mina swap names—and this isn’t the only time this has happened. In this version, Lucy is the fiancée of John Harker and Mina is the daughter of Van Helsing who takes Lucy’s place as Dracula’s first victim.

One of my favorite interpretations of the character has to be Sadie Frost in Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. This adaptation sticks closely to most of the main beats of the novel, while centering on a romantic plot between Dracula and Mina that is nowhere to be found in the original text. Lucy’s story is very similar to the book, but her characterization is radically different. This is a far more outspoken, free-spirited Lucy than Stoker’s version. But I think this version of the character addresses some of those original themes of repression. Here, Lucy is not remotely repressed but a very outspoken, sexual being.

That creates a bit of different context when she actually becomes a vampire. Here, it’s not a matter of Lucy saying things she’s never said before, but saying things she has said before in a way that is now twisted by her undead transformation. Lucy’s vibrant redhead look in Bram Stoker’s Dracula can also be seen as a reference to the fact that in some areas of Europe it was believed that red-headed people were cursed to return as vampires after they died.

I’m also, honestly, a fan of Lysette Anthony’s more comedic take on Lucy in Dracula: Dead and Loving It. She’s an amalgamation of several incarnations of the character, including the Hammer and Coppola versions. Her appearance sticks closer to the novel as this is one of the few dark-haired Lucys we’ve ever seen on the screen.

I’m also, honestly, a fan of Lysette Anthony’s more comedic take on Lucy in Dracula: Dead and Loving It. She’s an amalgamation of several incarnations of the character, including the Hammer and Coppola versions. Her appearance sticks closer to the novel as this is one of the few dark-haired Lucys we’ve ever seen on the screen.

This version is interesting because she has that public persona of being quaint and proper, but displays a personality more akin to that sexually charged Lucy seen in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Hints of this can also be seen in Tod Browning’s 1931 Dracula, which I think is another thing that this parody is attempting to point out.

By the time Dracula 2000 rolled around, a contemporary version of Lucy—played by Vitamin C—was once again relegated to the role of best friend, without terribly much to do on her own.

By the time Dracula 2000 rolled around, a contemporary version of Lucy—played by Vitamin C—was once again relegated to the role of best friend, without terribly much to do on her own.

The 2013 NBC Dracula series offered a great new take on the character, however. Katie McGrath’s version of the character was explicitly portrayed as a lesbian and actually in love with her best friend, Mina. This interpretation plays into subtext that has always been present in the character, dating back to the original novel.

Each version of the character offers something unique and different, but there is connective tissue between each and every one of them. Lucy is in some ways one of the more simplistic characters in the original story, but I personally think she is easily one of the most complex. Not only is Lucy the character who is always the most explicitly blossoming into adulthood, the one who is making the clearest attempt to kickstart her adult life, but she is also in many adaptations the only major character who actually dies.

Lucy’s legacy in pop culture is as the perennial victim, but I think there’s much more to the character than that, and you can find at least a spark of it in almost every version.