C. Courtney Joyner is an icon of the video era of horror movies. He has written amazing, cult classic horror films like Prison, From a Whisper to a Scream, Class of 1999 and Puppet Master III: Toulon’s Revenge. As a director, he’s helmed Full Moon hits like Trancers III and Lurking Fear, an H.P. Lovecraft adaptation that’s about to hit Blu-ray for the very first time.

He’s also an accomplished author, having written several Westerns such as Shotgun and contributed to several anthologies, like the industry-themed collection Hell Comes to Hollywood.

We talked to Joyner about his work on Full Moon’s Lurking Fear and its upcoming Blu-ray, as well as his long history with the Puppet Master franchise and more.

Wicked Horror: To go all the way back, you got to write for Vincent Price on your very first movie, From a Whisper to a Scream. What was that like?

Courtney Joyner: Well, the thing was, Jeff Burr and Darin Scott and I all went to college together. After USC graduation, we were all trying to do some things, Jeff was working for Jim Wynorski at the time and Darin was working for Robert Gamble. I had started an association with a TV director at Universal named Virgil Vogel, and Vogel was directing things at the time like Miami Vice, Matlock and Airwolf and all that stuff. I was actually working with Virgel doing director’s revisions on TV episodes.

But we all wanted to make a feature. This was at the time when you could certainly put together a limited partnership financing, go out and raise limited money, and go out and make a movie. And of course, in the wake of Halloween and Friday the 13th, low budget horror was very big. It was also the VHS boom and everybody needed product so it was really the perfect storm for this to happen. We decided to do an anthology because of the aesthetic we loved, we all loved Tales from the Crypt and Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors and all that stuff, but there was also a practical reason as well.

We felt that if our money was short, at least we could have the episodes and have something complete unto itself to show potential investors, instead of getting stuck in that thing where you have something three quarters of the way done.

WH: My God, that’s smart.

Joyner: Yeah! If you go back and the actors are a certain age and somebody’s dead, then it turns into a mess and this way we’d have something cohesive. Jeff Burr always wanted Vincent Price. He was fixated on that. And I was a naysayer, I said “Come on, Jeff, we’re never gonna get Vincent Price.”

But we were assembling this wonderful cast of people that we knew. I knew Clu Gulager quite well and introduced him to Jeff. Terry Kiser through a director I knew, Steve Carver. Jeff and I, we got Adolph Caesar because we went to Robert Aldrich’s memorial at the Director’s Guild and he was sitting in front of us. We just start talking to him! [laughs] Jeff got Vincent Price’s address from an old celebrity address service that you had to put two dollars in and they send you this thing in the mail.

He was not that interested. He had done the anthology series for PBS called Mystery with Diana Rigg, and that had been a great success. It was very prestigious. But he had also done The Monster Club, which was the Amicus thing, remember, where they did all of the little stories, with John Carradine?

WH: Oh, I do.

Joyner: And that had not turned out well. And he wasn’t too happy with that, so he kind of wanted this to just lie, but he was very polite. But what we asked him to do was let us go and make some stories and then we’ll come back and if you like any of it you can be in the wraparound. So he left that door open. So that’s what we did, and we came back, his agent was Walter Kohner, one of the great old style agents. His brother, Paul Kohner was John Huston and Lon Chaney Sr.’s agent. That’s how far back they all went.

So they came and saw some of the footage and Vincent signed on. The only bump in the road was, after we got him, we took it upon ourselves to do some rewrites and we wanted to take as much advantage of him as we thought we had. He was on a cruise and he got upset with us, because he felt that we were trying to keep him out of our creative process, basically. And we were just naïve. We were kind of fumbling around in the dark.

But he came back, came down on the set, met Clu Gulager, met Rosilind Cash, Martine Beswick, all these people who were old friends of his. And he met us and decided to go ahead and do the movie. And, kind of an interesting grace note to all this, originally—because he was an older man, then—I had had the Susan Tyrell character poison him. And when we got into it, Vincent was fine. But he wanted to make a script suggestion, so we were like, “Great!”

“No,” he said, “I think she should stab me in the throat, it’s much nastier.” So that’s what we did, but that was his idea. The only mistake we made was just in our enthusiasm, not letting him contribute to what we wanted to do.

WH: And after that, how did you get started in writing for Empire and Full Moon?

WH: And after that, how did you get started in writing for Empire and Full Moon?

Well, a friend of mine named Mike Farkus from college, his dad had been one of the investors in a movie called Hell Night with Linda Blair. Mike was at the time working for Irwin Yablans and Bruce Cohn Curtis right after college. And Mike had an idea for a futuristic prison movie. And I wrote him a treatment. I was actually working with him on a TV series called Lady Blue. Mike, while he was working for Irwin, Irwin had had this idea called Horror in the Big House which he had developed when he was over at Lorimar. They wanted someone to rewrite it and Mike said “Oh, a friend of mine wrote a prison thing for me.”

So he introduced me to Irwin and Bruce. I had a horror script called The Night Crawlers that they read, they liked it well enough. So then they hired me to write Prison. The writer that Irwin had hired before me, he was a TV writer, and he had told Irwin “I want to do Halloween in a penitentiary.” The guy is taking him literally, so it was a prisoner knifing other prisoners. Well, that only happens five hundred times a day. So I said, “Irwin, it can’t be that, it has to be supernatural.”

I said “It has to be Poltergeist goes to jail.” That was it. I wrote the project, then Irwin and Bruce split their partnership. Bruce ended up with some properties, Irwin ended up with some, and originally after that split up, the movie was gonna be done at Cannon. So we were with Menahem Golan and all those guys, then it was going to be Dino De Laurentiis. And we thought, “Wow!” So we’re having these meetings at Dino’s and for some reason that didn’t pull together. Irwin, of course, his old company had distributed Parasite and he knew Charlie very well. He walked Prison into Empire Pictures and also took an executive position on the movie, and that’s how that happened.

Empire was certainly not the first stop, although I was very happy with what we did. It had more money than what Charlie was normally allocating, but that was my start with Charles Band and the family and the whole journey there.

WH: How did you come into directing and doing Lurking Fear? Had you always intended on becoming a director?

WH: How did you come into directing and doing Lurking Fear? Had you always intended on becoming a director?

Joyner: Oh, yeah, I had always wanted to. But I had directed Trancers III before I directed Lurking Fear. But that was kind of part of it. After Prison, and we did well with it, Empire folded and Charlie went to form some other companies and make other movies elsewhere, and I was off and I wrote Class of 1999, working at different places around town, including Warner Bros.

But I hadn’t seen Charlie in a few years and a friend of mine had an audition at Full Moon. So I tagged along, I see Charlie in the hallway, we have a great talk and I see his dad. I loved Albert Band. He was such an icon. We spoke and he asked me to come down, he was shooting Trancers II at that point. He asked me if I would write Puppet Master III and two other movies and we would just make a deal for three scripts. And I said yes, and I had talked about directing to Charlie before and said “I want to direct one of these.” Apparently, they had been discussing this among themselves.

Albert had said, “Well, if Courtney directs let me produce it, so that if he runs into trouble I’ll be there.” All of this was going on behind the scenes and I didn’t even know it. So I wrote Puppet Master III and that turned out well, and Paramount was very happy with it, then we did Doctor Mordrid and that did well for Paramount and it had the association with Jack Kirby and all of that stuff, and then the subject of Trancers came up. The other thing there, of course, was that I had written a movie that Tim Thomerson was in already, so Tim and I were great friends. He really… he barn stormed for me, there’s no other way to put it. But Charlie and Albert were already leaning towards this, so he just went in and said “Look, I’m the star of this show and I also would completely support Courtney directing this.”

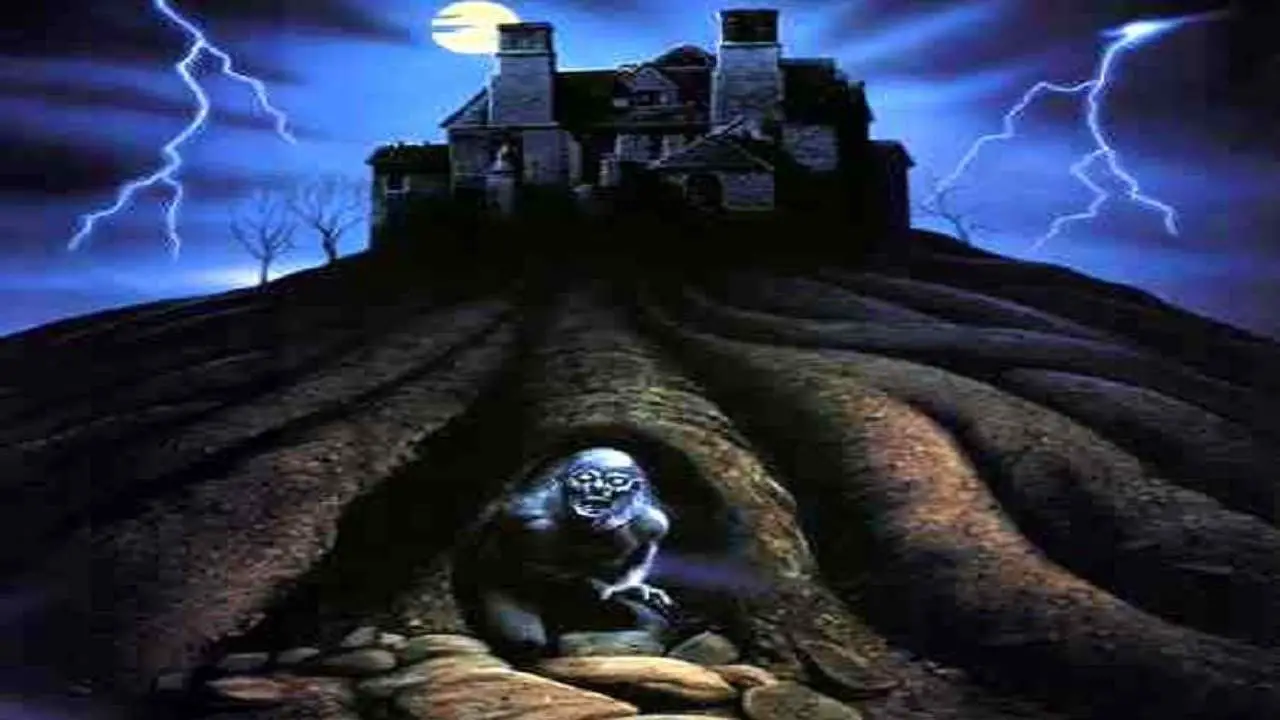

He really stepped up to endorse me, which was nice. I could not have had more support, just a kind entrée into directing than I did on that movie. It was terrific. Then, when the film was done and Charlie was happy with it, Lurking Fear had been a project of Stuart Gordon’s. Naturally. He was off doing something else, of course this was just after Honey, I Shrunk the Kids and things like that, so he was off at Disney and still continuing his projects with David Mamet and folks like that.

So it fell to me. Charlie wanted to do another Lovecraft thing, they said “go.” I never read Dennis Paoli’s script. I think it was set in the ‘30s. In fact, I was thinking about this just the other day, I had always had a certain approach because… well, have you read the short story?

WH: I have, yeah.

Joyner: Yeah, like a lot of Lovecraft stories, it’s first person and it’s the “these are the horrible events and here’s why I’m insane now.” That kind of structure. Expanding that, I wanted to do it as sort of a one man show, basically. A friend of mine named Brian Taggert did a movie I just got a huge kick out of called Of Unknown Origin. Do you know the movie?

WH: I do!

Joyner: Yeah, that was my starting point, Of Unknown Origin. We’ll have one guy, the Martense creatures are running around the house and he can’t find them, he’s going crazy and he doesn’t know if it’s a delusion or not. So I thought that was a great way to do it. But I got stuck. I couldn’t expand it beyond a certain point. Because the short story, as you know, is very slight. I was really chasing my own tail, and that’s when I decided to go with the crime structure.

I had already kind of done horror/noir aspects with movies like Prison, but it was comfortable for me, so that’s why I took the direction that I did. I just hit that wall that I think a lot of people who try to adapt Lovecraft hit. You can only expand things just so much when there’s only so much material to work with.

WH: That was actually a question I had, thinking that the best Lovecraft adaptations took really big liberties with the source material. His structure doesn’t lend itself to film on its own, you have to figure out ways to do it.

WH: That was actually a question I had, thinking that the best Lovecraft adaptations took really big liberties with the source material. His structure doesn’t lend itself to film on its own, you have to figure out ways to do it.

Joyner: The movie isn’t held in high regard–I always liked it–but Die, Monster, Die really is surprisingly close to “Colour Out of Space.” It is, but of course it’s a longer piece. And Dunwich Horror, again, kind of on that cusp. But Richard Matheson, he was a genius, to be able to take a poem and turn it into a feature screenplay. That’s a skill that probably very few of us possess.

WH: The creature designs in Lurking Fear are amazing. Those were what really struck with me, seeing this advertised when I was a kid. How much design input did you have on that?

Joyner: Absolutely, Wayne Toth is a great friend and what I wanted to do, one of the things I wanted to do that I always thought was so striking… remember the dwarf with the split palate at the end of Dario Argento’s Phenomena? I started there. I always thought that was such a simple, interesting makeup and of course it affects people because it’s actually a true affliction, but I always thought that was a wonderful visual. It was that and I love Bernie Wrightson. So Wayne and I sat there and we talked about the great comics Bernie was drawing for Eerie and Creepy and Vampirella, and he had a way of constructing the faces of his monster characters. Sometimes the nose was concave or not even there. And the jaw kind of went back behind the ear and was sharply distended, I said “That’s what I want.” And we kept looking through comic books and Wayne, he just nailed it.

WH: This year is also the 25th anniversary of Puppet Master III. David DeCoteau has chalked the success of the movie up to what he calls a “director-proof script.” Speaking from a personal perspective, I think it’s Full Moon’s best movie. I’m curious as to how that project and in particular your approach to crafting that story came about.

Joyner: Well, David’s very kind. He’s a good friend. David was actually producing for Charlie then. He was producing Crash & Burn and he was producing Trancers II, and when Charlie asked me to do it, he said he wanted to do a prequel to the first movie. And I had just seen Puppet Master II which David had also produced. He wanted to set it in World War II. I got excited about that. The first thing out of my mouth was “Oh my God, this is great! This will be the Where Eagles Dare of Puppet Master movies!” Nobody knew what I was talking about.

I said to David, “let’s make this a Pinewood Nazi movie.” David came over to my apartment and I loaded him down with tapes, and he watched Where Eagles Dare and particularly Night of the Generals and those great 1960s World War II flicks with all the British actors and we wanted to capture that flavor.

The movie was also going to be one of the first ones for Full Moon to shoot in Romania.

WH: I had heard that that was initially the plan.

WH: I had heard that that was initially the plan.

Joyner: That’s true. I was writing it along those lines, thinking of the sections of Romania that were kind of torn down. Just going off what I imagined, I hadn’t been there yet. When that didn’t happen and we ended up at Universal, I think that just elevated everything. David was completely responsible for our being able to shoot at Universal. That was his idea and he and John Shue Wyler got ahold of some folks and I was so excited. The only thing… here’s the sad part.

Okay, we really wanted an all European cast. So we have Ian Abercrombie and Walter Gotell and Sarah Douglas and all these people. It was just really shaping up very, very well. I was pleased with what I did. I thought I had gotten into the groove of the other Puppet Masters and I knew we were going to have our glorious friend there, Mr. Sardonicus, Guy Rolfe. That was great fun and I was very excited about all of that. The thing was, for the S.S. Officer who turns into Blade, David and I both wanted Ralph Bates.

We made an offer to Ralph Bates not knowing that he was in the hospital about to pass away from cancer. And he did. But he knew we had offered him the movie.

It was very sad, but we felt good that he knew somebody wanted him. Literally the next day, Christopher Neam, the actor from Dracula A.D. 1972 came in, big man, and he knew about so much of this, he said “If you hire me I am going to donate my entire salary to Virginia Wetherell,” who was Ralph Bates’ widow. Because Ralph was one of his best friends.

So I thought that was great and of course there are all these connections for me and David emotionally for films and all of these things, and it was all sitting right there in our office. Plus, what we thought would be a lovely, good deed.

But Charlie came in and he kind of said, “No, we really can’t have another European actor because it would hurt my sales.” He said “If we cast another person who’s not an American, the distributors will think the film was not made in the United States and not made by an American company and it will hurt the price that I can get for it.” He had just had Richard Lynch in the second Trancers, so he was fine.

And Richard ended up being good in the movie. He was a nice man, so that worked out well. But we had sort of an emotional sidetrack there that I think would have been nice for us to fulfill. And the thing is, with Richard, he looks exactly like that puppet. That was a real plus factor.

WH: So you were given the fact that it was going to be a prequel and it was going to be in World War II, how did you approach the idea of giving these characters origin stories?

WH: So you were given the fact that it was going to be a prequel and it was going to be in World War II, how did you approach the idea of giving these characters origin stories?

Joyner: That really was me trying to tie up loose ends. Since the appearance of the puppets was so distinct, and the idea of the soul transference and all that stuff, I said “Well, if we’re fighting Nazis they should be people who had died fighting Nazis.” Something along that line. People who were involved in the underground with Andre Toulon. I thought that was a good way to kind of lace all of this stuff together. He wasn’t just this man with puppets that came to life wandering from pillar to post.

I thought, “No, this is his mission.” He has created his own private army to fight this evil. That was also the thing with Six-Shooter. As you know if you’ve seen that old Empire material, Six-Shooter was created for another movie, I want to say Eliminators. It was another Empire project that wasn’t made, but the design was of a black metal warrior. But without a head. It was like the robot suits in Earth vs. the Flying Saucer, with six arms, and black. So Charlie wanted to include that puppet because he’d had Torch in the second movie and we didn’t want to fool with Torch again because of the fire.

Charlie just said “We’ll use Six-Shooter,” and I went “OK.” Then I said, “No, he has got to represent something.” The other puppets are part of Toulon’s past, they are people he knew, he’s anointed with this power, like his wife’s soul going into Leech Woman, then Six-Shooter needs to represent something. So that’s why I turned him into a cowboy. This is the idea of what America was at that time. Certainly it’s the idea Europeans would have because of Westerns. That’s why I chose that. And to see him shooting at the Hitler puppet, that was great.

WH: Yeah, that whole idea just adds depth. And with Puppet Master vs. Demonic Toys, that was a project that Full Moon had been kicking around for years. Did you work off any previous drafts of that script or did you start completely from scratch?

Joyner: No, I didn’t. When that thing started it was going to be specifically for the Sci-Fi Channel, for a producer who had done very well with Full House and some big television shows and it was to be shot back-to-back with a movie called Man With the Screaming Brain that Bruce Campbell was directing. And the idea was that it was going to be a pilot for a Puppet Master television series. But they wanted it to feel like Gremlins and to have that kind of tone to it.

So the Andre Toulon cousin or whatever it was supposed to be, was actually written if I remember correctly, for Martin Mull. And so… OK. They cast Corey Feldman. And I said “That’s fine, but the part needs to be rewritten so that it’s age specific.” He can be the grand nephew, I don’t care, but he’s not a sixty-year-old man. And then they kind of went in this odd direction, I was never quite sure why they did it, but they actually spent a little bit of money on that. And Ted Nicolau, I actually thought Ted did some very interesting sequences.

Things like little robots and monitors and all that stuff, that’s usually the type of thing that gets cut immediately because it’s too much of a hassle. And, wowee, I got a write a movie that Vanessa Angel was in. But it was a shame because I think it could have worked and had a bit more of a life if it had been properly cast. And I actually ran into Corey Feldman about a year or two later and he came up to me and goes “I’m sorry, man, I’m sorry.” And I said, “Hey, it happens, don’t worry about it.” But Charlie turned that entire project over to the Sci-Fi Channel and I worked directly with those guys.