Tobe Hooper’s Salem’s Lot is not only a seminal vampire movie but a great Stephen King adaptation as well. It has held up for over thirty-five years and is remembered as a classic, which is pretty astonishing because there’s no real reason that the movie should have been good.

Stephen King wasn’t at the level of fame he is now when Salem’s Lot was published and had only just broken through when it was being developed as a film. He had had only one screen adaptation at that point and while Carrie was a great success, he was hardly a household name. This wasn’t a time when King’s involvement was enough to ensure the success of a project. In fact, it wasn’t even the rising success of King that got the project green-lit. It was put into development following the announcements of John Badham’s Dracula and Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu.

Initially, Salem’s Lot was going to be developed as a feature by George A. Romero. This would have been just after Romero’s own innovative vampire tale, Martin, and just before the massive success of Dawn of the Dead. Romero’s script was very faithful to the source material, which was incredibly dark, but the scope of the novel was difficult to condense into to a single film.

Ultimately, Warner Bros. decided the project would be better suited to the length of a cable miniseries. At that point, Romero left the production, believing that he would not be able to make the film the way he wanted to within the restrictions of network television.

In fact, during this time Hooper’s output was pretty bad and it didn’t bode well for Salem’s Lot to have him step on board after Romero had walked away. The next couple of movies Hooper made between Salem’s Lot and Poltergeist were pretty terrible too. More than anything, this makes Salem’s Lot an anomaly during this period in Hooper’s career. There’s nearly no reason for it not to be bad.

Romero’s reason for leaving was perfectly sound. He thought that he would not be able to bring his vision for the film to life and adhere to the censorship standards of network TV, which is reasonable. Salem’s Lot is a very gory novel. It’s a very adult novel and it’s easy to see why it would be hard to imagine trimming it down. Making Salem’s Lot for television meant making it with none of the visceral elements intact. That alone should have spelled doom for the production.

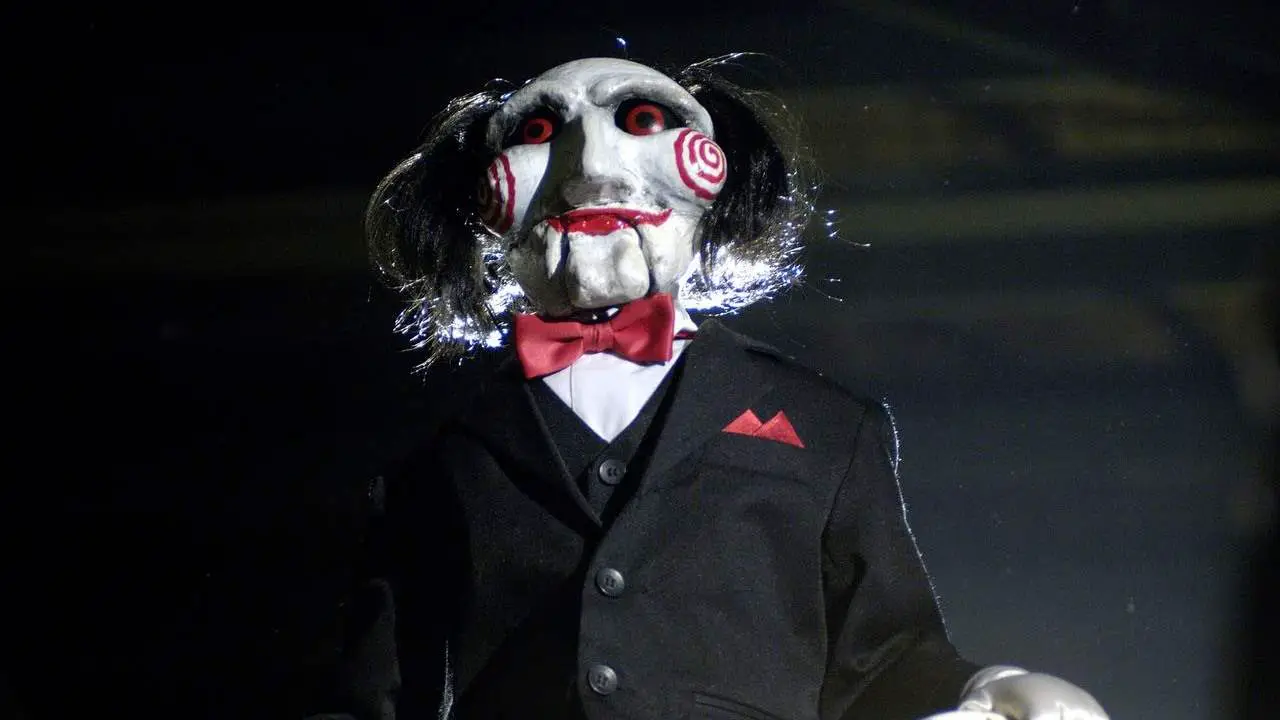

Tobe Hooper also insisted on a few drastic changes to the material, one in particular that stood out. He wanted to change the lead vampire, Kurt Barlow, into a silent Nosferatu-like character. In the book, Barlow is a fairly eloquent, suave monster. It’s surprising that Warner Bros. allowed him these changes given the reasons they decided to make the picture in the first place.

Tobe Hooper also insisted on a few drastic changes to the material, one in particular that stood out. He wanted to change the lead vampire, Kurt Barlow, into a silent Nosferatu-like character. In the book, Barlow is a fairly eloquent, suave monster. It’s surprising that Warner Bros. allowed him these changes given the reasons they decided to make the picture in the first place.

They wanted something that would match the tone and hopefully success of John Badham’s Dracula, which was ushering in the age of the romantic vampire. Even Herzog’s remake of Nosferatu, while keeping the vampire similar in appearance, brought a much softer personality. Hooper wanted to take vampires back to their monstrous roots and surprisingly the network agreed.

What we got was one of the few iconic monsters to be birthed in a telemovie. In fact, the only other that would qualify would be Tim Curry’s Pennywise in the adaptation of King’s It. The image of silent, menacing, rat-like Barlow haunted viewers for decades.

Salem’s Lot was so successful that a drastically recut version—in order to accommodate length—was released to theaters. It was the only television miniseries to undergo such treatment and be shown in theaters, and it remains so to this day. But on paper, none of the ideas mesh. Nothing sounds as if it would work, but it all did. Yes, it suffers the budget of a made-for-television production.

Salem’s Lot was so successful that a drastically recut version—in order to accommodate length—was released to theaters. It was the only television miniseries to undergo such treatment and be shown in theaters, and it remains so to this day. But on paper, none of the ideas mesh. Nothing sounds as if it would work, but it all did. Yes, it suffers the budget of a made-for-television production.

It’s not as gory as the novel, but what it lacks in gore it more than makes up for in pure atmosphere. The sight of a shining, silver-eyed vampire scratching at the window to be let in proved to be more terrifying than any decapitation. It was the shot in the arm that Tobe Hooper’s career needed, and even though he was still riding and would continue to ride the success of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, it’s reasonable to think he may not have gotten the job directing Poltergeist if it weren’t for the way he had taken this unworkable project and simply made it work.