*The following post includes discussion of racism and sexual abuse*

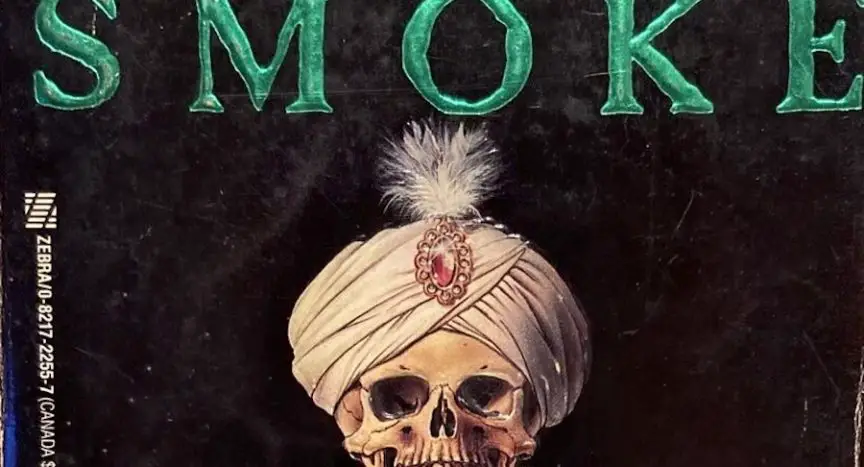

Notorious among horror fiction aficionados are the horror novels published by Zebra in the 1980s. Just hearing the name is enough to conjure images of cover artwork featuring a skeletal figure that definitely won’t be part of the narrative explored within its pages. Gary Hendrix’s book Paperbacks From Hell discusses the horror boom of the ’70s and ’80s and even makes a point to analyze the trends within Zebra’s horror titles.

My first exposures to Zebra Horror came in two parts. First upon learning of the Nightmare Club series published by Zebra’s teen imprint in the 90s. Second in a hotel giftshop, seeing secondhand copies of Christopher Fahy’s Dream House, Joseph Citro’s Guardian Angels, and Stephen Gresham’s Rockabye Baby.

Admittedly, my own list of Zebra Horror titles is slim compared to other collectors. As of this moment I’m lucky enough to own:

- Guardian Angels by Joseph Citro (Actually the reprinted version)

- Night Stone and Little Brothers by Rick Hautala

- Smoke by Ruby Jean Jensen

- Toy Cemetery by William H. Johnstone

- Dew Claws by Stephen Gresham

- The Dollkeeper by Jack Scaparro

As well as teen horror Halloween Party by Wendi Corsi Staub and Spring Break by Nick Baron (unofficially considered part of the Nightmare Club series).

Smoke is my most recent addition after struggling to find a copy with the original cover art being sold at a reasonable price. This is my first exposure to the late Ruby Jean Jensen’s skills as an author, although I had an idea of what to expect from poring over some of the reviews.

And, I must admit, while struggling with the passing of my own mother, the fact that motherhood is a key component of this story certainly informed my perspective.

Smoke’s initial summary speaks of Ellen, a little girl who finds what she thinks is a magical lamp. When Ellen rubs the lamp, what comes out isn’t a genie. Instead, people start dying and Ellen takes the blame. This is misleading on two accounts. The entity Ellen frees isn’t a genie, though it’s considered one by the characters. It doesn’t grant wishes and doesn’t consider Ellen its master, though it follows her and her siblings Beth and Joey throughout the story. Second, scrutiny gets placed on Ellen and her brother and sister for most of the book after the first murder.

What really happens is this:

7-year-old Ellen Penderghast buys an old lamp at a garage sale. When Ellen rubs the lamp thinking a genie will appear, it unleashes a murderous spirit that brutally kills Ellen’s mother. Ellen, her sister Beth, and brother Joey are sent to live with Faye, their father’s new wife. It’s a big adjustment for everyone, as Faye is also pregnant with their baby sibling. Unfortunately, because no one saw anyone enter or leave the house and the doors were locked from the inside, people have suspected the Penderghast children murdered their mother. Even when Gavin though it’s revealed that their mother was violently raped by her killer, some people still think the children were responsible.

Ellen’s stuck living in a constant state of fear, haunted by vague memories of what was done to her mother. The creature that murdered Ellen’s mother follows the children to their new home, disguising itself but haunting Ellen specifically. It’s only in the presence of fire that the creature fully manifests, killing victims lighting a cigarette. Beth, initially thinking Ellen did kill their mom, also becomes aware of this entity which Ellen calls “The Monster.” While Beth struggles to protect her brother and sister, Faye also struggles to protect the children while accepting them as her own.

Before I go further, I need to openly discuss the racist caricature that Ellen’s monster is. Smoke’s prologue establishes this spirit was an Asian man from the 1800s, a morbidly obese child rapist who died when a young girl started a fire using the very lamp Ellen obtains. The imagery of “slitted eyes” is repeated throughout Smoke, as is mention of how incredibly fat and repulsive the monster appears. There’s also the fact that Rhoda, the second victim, is all but outright stated to be a young Black woman (she refers to Faye’s neighborhood as “Honky Town”) who happens to be an unwed teenage mother who dies after lighting a joint. She only appears for a few pages before she gets killed, with no mention afterwards of what happens to her own mother and her two children.

I’ve no desire to defend Ruby Jean Jensen’s treatment of Black and Asian characters, even if I’ve chosen to write about this book. I’ve long been aware that Smoke doesn’t really have a positive reputation among critics. Truthfully I came into this thinking it would be far more sexually exploitative and gratuitous. So I can’t, in good conscience, openly suggest this book to other readers with that in mind. I can, however, talk about the presence of Smoke’s female characters and how fittingly the title works in a way I didn’t expect.

With the repeated mention of a magic lamp, I expected Smoke to be a typical genie horror story almost like Wishmaster. The summary’s discussion of Ellen being viewed as “a bad seed” gave me an idea of how the Child’s Play franchise treated Andy Barclay. I suspected Ellen would either carry the lamp with her throughout the story, despite knowing it was a source of evil, or it would keep reappearing despite her attempts to get rid of it. Instead, while the lamp is mentioned thoroughly in the summary and the cover art, it vanishes up until the end. Its only function was to release the villain who is free to haunt the Penderghast children wherever they go.

Ellen, her sister Beth, and stepmother Faye are the ones who really drive the story forward. Beth and Faye attempt to act as guardians for the Penderghast children in different ways. When Smoke kicks off, Beth erroneously believes Ellen killed their mother when she follows the trail of blood to Ellen’s bedroom and finds her little sister drenched in it. Thankfully, Smoke doesn’t waste as much time on this when Gavin Penderghast, the children’s father, must explain what really happened to his wife. From there, Beth devotes herself to sheltering her brother and sister. She doesn’t exactly trust Faye as a mother figure, but it comes more from the idea of Faye as a stranger. Jensen shows that Beth’s devotion to her siblings is admirable, but her actions don’t really help their situation until she starts being honest with Faye. However, Beth’s actions can be understood for a girl of her age and due to the supernatural predicament she’s caught in. It’s not that she’s stupid, it’s that she doesn’t have a way to explain what’s happening and she’s not sure what else she can do. As the oldest, she feels she needs to be the one who protects her siblings.

Faye, for her part, realistically struggles to adapt with suddenly having three grown children in her life. While she’s made attempts on her own to get to know her stepchildren (which both them and their birth mother have shot down), there’s the fact they’ve now become permanent parts of her life in a way she could’ve never anticipated. Not to mention her own child with Gavin hasn’t been born yet. Nevertheless, Faye does the best she can to make a home for the children while understanding they aren’t simply guests until she finally declares that they ARE her children no matter what anyone says, and she won’t allow anyone to come between them if she can help it. There’s a sweet moment later in the book where Faye reveals she’s washed Ellen’s beloved rag doll, the one source of tangible comfort Ellen’s had throughout this nightmare.

The cloud of suspicion hovering over the Penderghast children gives Faye more incentive to become a mama bear with their mother dead. Faye is legitimately disgusted that people, like her neighbor Nordene and her sister Janet, actually believe Ellen and her siblings could’ve murdered their own mother. It’s only when Faye has to tell them that Blythe suffered through “extreme sexual mutilation” that the suspicion is quashed, but the Penderghast children are still met with wary expressions due to the horrors following them around.

Finally, there’s Ellen who unintentionally frees this horror–and later has to be the one to end it. Jensen treats Ellen as a child without making her particularly childlike nor too smart for her age. She tries to tell people about “The Monster” that killed her mother and has been following her family. While the summary lies about Ellen being seen as “a bad seed,” she does receive the most scrutiny of her siblings. Even if no one is really willing to think a seven-year-old girl could’ve done… that, to anyone, by the end of Smoke people suspect her of being mentally ill and requiring psychiatric care.

It is mother and child who eventually bring Smoke to a close. Beth being the one to figure out how to stop the monster, Faye being the one who has to bring them to the source, and Ellen being the one who starts and ends it. I wouldn’t call Smoke feminist but Jensen still has her female characters trying to take charge of where the story goes.

The true horror of Smoke is more in the way it lingers from chapter to chapter. Jensen sets up sequences where characters can smell smoke in the air, to remind us the creature is with them. Beside the exaggerated form mentioned previously, the creature also appears as a large cat and a red flame at various points. It kills its victims in the same way, through violently raping them and essentially tearing them apart. However, Jensen never gets explicit with the way this is done. We’re treated to the creature overpowering its victims as it manifests through the smoke and then cuts back to after they are dead, thankfully – or maybe not so thankfully – leaving it to our imaginations.

No, the way the horror works in Smoke is how the creature’s evil saturates the surroundings and the characters. The Penderghast children suffer because of what the creature did to their mother, tainting them with its presence wherever they go. People like Faye’s neighbor and her sister are both aware that something keeps following the children, but they aren’t aware of what needs to be done to stop it and assume it’s the children themselves who are the problem.

A lot of focus is spent on Nordene’s unease around Faye’s stepchildren, but she’s unable to truly comprehend the situation in a way that helps. Nordene herself is driven by a desire to protect her own children, Dwayne and Katy, from whatever is around the Penderghast kids. Faye’s sister Janet meanwhile tries to get her away from the Penderghast kids for good, fully assuming they are the problem and fearing they will be the death of Faye and her baby. It’s a reflection of Beth’s interactions with Ellen. Beth and Janet both fear for their sister’s wellbeing, but they don’t really know what’s best and end up causing more harm than good. The difference being that Beth is willing to admit when she’s wrong while Janet holds onto her belief she’s doing the right thing for Faye.

It’s a sort of indirect and insidious possession, as the creature isn’t directly controlling the children it is still responsible for poisoning them and how others see them.

A counselor introduced just before the book ends is the only one besides Faye and the kids to realize it’s an invasive entity that is haunting the children, not the children themselves, that needs to be dealt with.

As the evil of the creature lingers, it causes tension as you wonder what’s going to happen next. Immediately following the death of Nordene, there’s an entire sequence where Ellen and Nordene’s daughter Katy return to Nordene’s home to get snacks for a picnic. Throughout this whole exchange, you keep expecting the girls to eventually find Nordene’s dead body or be led to it. It doesn’t happen and they leave the house unharmed, but it’s unsettling to understand Nordene was dead the whole time they were in the house and they didn’t realize.

Jensen’s pacing can be a problem. Sometimes things happen too slowly, sometimes they happen too fast. The ending comes across as rushed and the counselor’s appearance and understanding of the supernatural feels a bit out of left field. As this is the only novel I’ve read by Ruby Jean Jensen, I’ve no idea if the counselor appeared in any of her other books. I have a sense some of the Zebra horror novels might have shared universes, such as Stephen Gresham’s Dew Claws and Moon Lake. I don’t know if that’s the case with Smoke and Jensen’s other novels, though.

While I can’t fully recommend Smoke to casual readers without pointing out the racist depictions, I admit Jensen’s characters gave me more to think about then I expected of this book, which is why I wanted to talk about it. What kept me interested was Faye’s role as a mother and Beth’s attempts to handle the situation. Enough so that I’m willing to give Jensen’s other novels a try.