There was a lengthy period of time when Hellraiser II was considered one of the best horror sequels of all time. I’ll readily admit that I discovered it during that time and it probably colored my expectations of it, but I was blown away. I’ve always championed it as one of the best horror sequels out there. In recent years, it’s lost that acclaim. Even Hellraiser fans tend to lean on Bloodline and Inferno a little more heavily now. In some ways, though, I understand the gradual backlash or loss of interest. While Hellraiser II is still regarded for its ambition—as well it should be—it’s criticized for one major, key element: It doesn’t make sense.

Well, it does if you dig deep or read supplemental material to have it explained to you, but if we don’t give Prometheus a pass then Hellbound shouldn’t get one either. But the thing that I think a lot of people miss is that this movie isn’t necessarily supposed to make sense—or, at least, it’s supposed to operate on a different kind of logic because, after all, we’re dealing with Hell. The selling point of Hellraiser II is that we go head-first into Hell itself instead of only seeing a single corridor as we did in the original.

The returning characters carry on perfectly well from the first. There’s nothing lost in characterization, which is why I think the sequel doesn’t lose itself in playing with surrealism. We still care about what happens to the people involved. We’re fully on Kirsty’s side from the beginning because we’ve already been through this with her before. Julia, meanwhile, has moved on from being a somewhat morally conflicted antagonist to a full-fledged villain. Now that she’s stepped into Frank’s role in the narrative, she immediately embraces it. She’s been through this before too, after all, if only from the other side.

I think it’s the film’s treatment of Hell that loses a lot of viewers, but that’s also my favorite thing about it. This is like no Hell we’ve ever seen in a movie before, and we’ve seen plenty. The Labyrinth is cold, not hot. It’s a maze of empty corridors and blank stone walls. It’s all painted in the same blue glow that follows the Cenobites wherever they go.

A lot of people are confused by how Kirsty abandons the search for her father, how Leviathan, which is supposed to be some kind of God to this section of Hell, is defeated by the simple solving of a puzzle. What even happens at the end, as it looks at first glance like Kirsty and Tiffany destroy Hell itself?

Did You Know? Wicked Horror TV Has Classic and Independent Horror Films Available to Stream for Free!

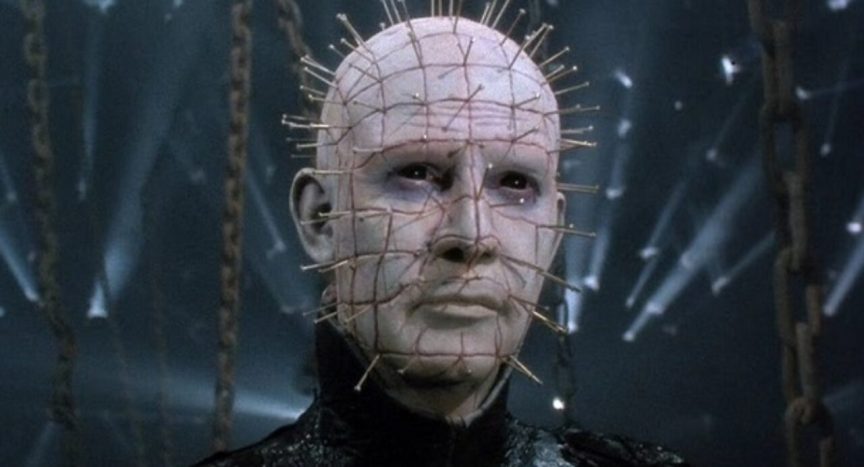

All of that comes from thinking of Hell as a tangible thing that operates exactly as our world does, when the film very much shows that that’s not the case. This is a totally different, spiritual realm and it operates on an entirely dissimilar set of mechanics. Once you step into the labyrinth, you’re stepping out of time and space. Pinhead perfectly sums up this version of Hell in conversation with Kirsty.

She tells him she’s come to rescue her father and Pinhead, in rare form, laughs in her face. He explains that “He is in his own Hell, just as you are in yours.” Because that’s all Hell is. We’re not even seeing the Labyrinth clearly at any given point, we’re only seeing what each individual character perceives it to be. That leads into my other favorite thing about this film, which is the shift that occurs in the third act.

Many people just become lost when Channard starts running rampant as a Cenobite and Tiffany suddenly becomes, well, hell-bent on solving the transformed puzzle box, which is now a diamond. It’s all very strange, but it unfolds organically. It ties directly back into the fact that Hell is a different thing to different characters. Once Tiffany comes into her own and literally finds her voice, we start to focus on her a little more and that’s also when the whole narrative structure changes in a kind of genius way. For Kirsty, Hell is a maze that she has to navigate, so we spend all that time with her as she futilely searches for her father. For Tiffany, though, Hell is a puzzle that she has to solve.

Hellbound is ultimately a movie about transformations. Some of them happen internally, some happen externally, more often than not, both things occur. When we meet Julia, she’s already transformed. She has to get her body back, but she’s changed on a fundamental and spiritual level. On a parallel note, we retroactively discover the event that led World War I Captain Elliot Spenser to become the Cenobite we know as Pinhead and subsequently learn that all Cenobites began life as human beings who solved the box, once upon a time. This is a fairy tale, after all. Once upon a time is a key part of the narrative.

Kirsty’s arc is internal, but kind of brilliant. She starts off hell-bent on finding her father, but if she actually saved Larry, it wouldn’t be as interesting. I feel like a lot would have been lost had Andrew Robinson returned, even as great of an actor as he is. It’s a much better reveal to discover that Frank tricked her into coming to Hell simply so that he could have her for himself. Even when her hopes are dashed, she doesn’t give up, because Kirsty’s role is ultimately about learning to care for this young girl.

Yes, Kirsty’s arc draws immediate parallels to Ripley’s arc in Aliens. The two are different enough to stand apart and even though Kirsty is also stepping into a motherhood role, it doesn’t mean that wasn’t the perfect direction to take the character in. In the first film, Kirsty is defined by her relationship to her father. They had a very close bond that is only strained by her contempt for Julia, the quintessential evil stepmother. At the beginning of Hellbound, all she wants to do is get her daddy back. There’s something inherently, but sympathetically, childish about that.

She steps into adulthood as the movie progresses by coming into her own and learning to care for Tiffany, who is the only person in the movie that comes into Hell as a total innocent. She didn’t necessarily come to it of her own free will, she’s the only one who didn’t plan to be there. She’s Alice, stepping through the looking glass, led on by her own curiosity.

The most drastic transformation in the film, of course, belongs to Channard. He’s a very quiet, sophisticated monster at the start, but a monster nonetheless. He’s a chilling nightmare of a man, arguably scarier as a human than he is as a Cenobite. But he’s still very stoic, very restrained. Once he becomes a Cenobite, he’s unhinged. Here’s a man who owns a mental institution, treating people day in and day out, secretly torturing and murdering them in his spare time. He spends all of his time taking advantage of the mentally ill and he does it only to hide the raving lunatic within.

When he’s dragged kicking and screaming into becoming a Cenobite, it turns out to be everything he ever wanted. Because it’s an excuse. No more suits and ties, no more need to hide his crimes in the sub-basement of his institution. As a Cenobite, he’s allowed to be himself. And what he is, it turns out, is a manic, destructive force. That’s a great transformation because Channard is led to Hell under the pretense of finally seeing it after so many years of research. But Leviathan and Julia have other plans for him, things he learns at the last second, things he’s terrified of. Even seeing his own crimes flashed back in his face is too much for him.

For Channard, becoming a Cenobite is like diving into a pool. You’re nervous. The water might be too cold, it could be unbearable. But once you’re in, you’re in, and you embrace it. But there’s a great, subtle twist that occurs once this happens. Leviathan and Julia, they’re the ones who want Channard to become a Cenobite, but once that happens he’s the one who gets what he wanted. And only him. Because after he’s fully transformed, he’s everything that the Cenobites aren’t. He’s an agent of chaos, not order, and he’s clearly intent on doing his own thing.

Hellraiser II is the perfect answer to so many of the fantasy films of the ‘80s, because it follows so many of the same tropes. But it takes the imagery further into a place of total surrealism. It’s still character centric, but it’s character centric to the point that the characters essentially define the world around them. That leaves you in a place where you never know totally what to expect. It’s Labyrinth by way of The Beyond. Not a combination you’d expect, but one that’s absolutely worth embracing.