On Wednesday, Nov. 28, IFC held a special one-night screening of the director’s cut of The House That Jack Built at select venues across America. It’s the exact same print that made people at Cannes vomit, protest and cheer their hearts out once it was all over. And considering how miffed the MPAA is over its content, it might be a long time before we’ll ever get our hands on this 152-minute cut of the movie again (there are even rumors circulating that the severely edited R-rated version of Jack, scheduled for theatrical and VOD release Dec. 14, might get yanked from circulation.) This very well could be the modern day equivalent of the infamous screening of the original 8-hour cut of of Erich von Stroheim’s Greed in 1924 — the only opportunity the general public ever got to see Jack in its fullest, most undiluted form.

I’m just going to get it out of the way now — The House That Jack Built (the director’s cut version, anyway) isn’t just the best horror movie of 2018, it’s the best movie of 2018, period. Furthermore, I’d argue it’s the best movie Lars von Trier has made to date, and quite possibly the single best serial killer movie since The Silence of The Lambs. It’s brutal and disgusting and insightful and poignant and gripping and unnerving and hilarious and thought-provoking and about 20 or 30 other seeming antonyms that shouldn’t be possible in one movie — but somehow, someway, von Trier managed to pull off the cinematically impossible. At my screening, when the end credits started rolling, the audience (made up of some of Atlanta’s most hardened and hardcore cinephiles) had no idea how to react. Some laughed, some looked like they wanted to puke, and others looked like they had just survived a nearly fatal car crash. As director von Trier himself said in a special message before the movie, Jack is a film meant to be digested over several days — and I don’t think anyone at the Plaza Theater on Ponce has stopped mulling the core essence of the movie since (this humble critic included.)

The thing that strikes me most about The House That Jack Built is how you can read it through so many different lenses. If you want to see the movie as nothing more than a slightly more high-brow slasher/splatter fest for the arthouse hipster set, you can certainly do so. But if you want to see it as a deeper, more philosophical psychological-drama – i.e., Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer — you can certainly do that, too. Hell, if you want to view it as a coal-black parody of horror movies and psycho murderer thrillers in the vein of Man Bites Dog, you can take that route as well. A movie as deep and nuanced and layered and multifaceted as Jack necessitates multiple viewings, and the mindset of the viewer can completely alter one’s perception and reception of the work. Sometimes The House That Jack Built feels like a straight-up “true crime” saga that could almost be labeled an expy dramatization of the Ted Bundy and Edmund Kemper stories, and at others, it almost feels like an absurdist pastiche of the serial killer subgenre — indeed, Jack may be as close as we’ll ever get to seeing a live-action adaptation of Johnny The Homicidal Maniac.

But it’s also a lyrical and poetic film, with a narrative structure pretty much on loan from the Aristotelian Dialectic. And the epilogue of the movie is literally a re-adaptation of one of the greatest works of literature in the Western canon, but I don’t want to spoil it for you. Then again, as soon as you learn Bruno Ganz’ character is named “Virgil,” well … it’s not really that big of a plot twist, is it?

The film relies upon the same framework von Trier utilized for his last film Nymphomaniac. You’ve got the main character “confessing” their guilt to an elder figure, who spends the duration of the picture analyzing and deconstructing their actions. The House That Jack Built is essentially subdivided into six major chapters, with bridges in between in which Matt Dillon’s eponymous character and Ganz wax philosophical on war crimes, violence in the arts, and “the noble rot” — among many other intriguing asides.

The “chapters” tend to focus on specific murders committed by Jack, with an occasional flashback and flashforward sprinkled into the diegetic salad just for the sake of being artsy-fartsy. Never one to shy away from the meta, at certain points in the film, von Trier even manages to juxtapose his own previous cinematic work over stock footage from concentration camps and the Idi Amin regime — feel free to make your own deductions on the veiled meaning he’s trying to get across there.

And if you think that’s gross, just wait ’til they show you what’s inside the bag.

I don’t want to give away too many details on the murder scenes, but by now you’ve probably heard the gist of it through the Interwebs. In the opening sequence Uma Thurman hops in a ride with Jack with, ironically enough, a tire jack. Without spoiling it for you, I can assure you that tire jack is used for several things, but changing a tire isn’t one of them.

The second chapter details Jack’s attempts to infiltrate a widow’s home, and how his obsessive compulsive disorder tendencies almost get him found out by the po-po. Chapter three reminds us all why it’s never a good idea to take your children on a hunting trip with a serial murderer, and part four reminds us why it’s never a good idea to a.) date a serial murderer and b.) let said serial murderer draw suspiciously detailed surgery markings on your body as a form of unorthodox foreplay. And the final chapter focuses on Jack’s homicidal magnum opus: an attempt to kill six people with a single bullet that, apparently, is a lot harder in practice than in theory. And of course, there’s that final stanza I was referencing earlier — needless to say, it takes on a tone and atmosphere totally unlike the rest of the movie, and despite the drastic stylistic shift, it remains every bit as harrowing and captivating as the preceding chapters.

Much has been said about the violence in the movie, with some accusing the film of promoting misogyny. Interestingly, this is something von Trier himself sort of lampshades in a scene where Virgil asks Jack why he tends to prey on female victims — and why they act so stupid. Anybody who’s ever taken a criminal justice course can tell you exactly what the director’s referencing there — Gavin de Becker’s seminal work The Gift of Fear, which actually encourages readers (particularly females) to be cognizant of their own surroundings and stay wary of strange (read: practically all) men. Clearly, The House That Jack Built isn’t a film that glamorizes violence against women, depicting such as horrific, brutish and decisively non-sexual. If anything, one might be more inclined to call “Jack” a quasi-misandrist work, with the main character practically the living embodiment of everything the #MeToo movement fears about the unfairer sex.

A picture of emotional stability, isn’t it?

As for the graphicness of the movie, I think The House That Jack Built is hardly any more violent than most R-rated Hollywood horror movies. In fact, I’d surmise that the latest Halloween sequel is an objectively gorier movie than The House That Jack Built but the difference is in how the latter makes the violence feel consequential. Jack is a movie that shows homicide as the visceral, unglamorous, sloppy, nonsensical transgression it is. When people get shot in this movie, their heads don’t explode in video game showers of blood and bone — rather, they crawl around as wounded animals, slowly and pathetically leaking their lifeforce across the screen. Whereas, other horror movies are content showing the active murder and then cutting away to the melodrama, Jack is a movie that lingers on the product of murder. This is a film that forces the viewer to stare at the lifeless corpses of children, to watch people gasp and gurgle and strain for breath and cry and beg for their lives. The average Saw movie has more blood and guts than Jack, but what Jack does is make the violence we do see feel realer, more devastating, more painful and more loathsome. Whether or not the onscreen mayhem presented in the director’s cut of “Jack” merits an NC-17 rating is in the eye of the beholder, but this much is certain — the death and destruction in this movie is far, far more disturbing than just about any other movie to come out in 2018.

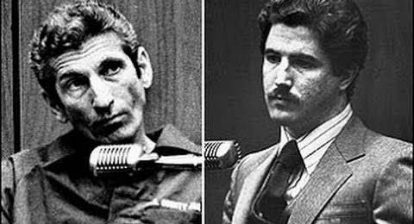

In a just world, Matt Dillon would be a lock for a Best Actor Oscar. His “Mr. Sophistication” is the most fascinating movie villain to grace the silver screen since Heath Ledger’s Joker, a character who is simultaneously revolting and appealing, alternating between unapproachably crude and oddly endearing. Dillon certainly did his homework here, with dead-on mannerisms on loan from real world serial killers like Richard Kuklinski and Jeffrey Dahmer. Dillon does a much better job portraying a charismatic emotionless psycho than Christian Bale ever did, and it’s apparent that either he or von Trier studied clinical sociopathy quite a bit in the lead-up to production. Martha Stout’s The Sociopath Next Door seems to be a clear influence on the main character’s persona, as is, perhaps the work of author Pete Earley — most palpably, The Serial Killer Whisperer.

Also See: Seven Horror Films That Should Have Won Best Picture at The Oscars

Even for hardcore horror enthusiasts The House That Jack Built might be too taxing an experience — if not for the up-close breast slicing and elementary schooler murder, than for the film’s intentionally (albeit effective) disjointed structure. Those with shorter attention spans and a complete disdain for anything philosophical or academic need not apply here; odds are, you’ll be tuning out long before Jack starts crushing people’s wind pipes and using their corpses as performance art props. But if you’re a fan of esoteric cinema, have at least a passing knowledge of The Divine Comedy and can appreciate movies that force you to interpret their core meanings on your own, The House That Jack Built isn’t just a must-see, it’s a you-should-have-been-there-on-opening-night-and-shame-on-you-if-you-weren’t.

Wicked Horror Rating: 10 / 10

Director(s): Lars von Trier

Writer(s): Lars von Trier, Jenle Hallund

Starring: Matt Dillon, Bruno Ganz, Uma Thurman, Riley Keough

Year: 2018

Release Date: Dec. 14 (R-rated theatrical and VOD)

Studio/Production Co.: IFC

Language: English

Length: 152 minutes (director’s cut)

Sub-genre: Serial killer, arthouse, psychological, satire